- Home

- Bruce, Leo

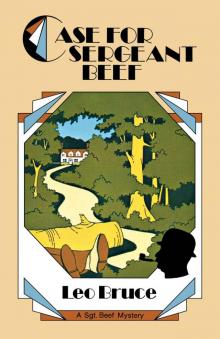

Case for Sergeant Beef Page 5

Case for Sergeant Beef Read online

Page 5

Mr Chickle seemed cross.

‘Place where I often go?’ he repeated frowning.

‘Yes, sir. You know, by the fallen tree. He’s dead. Half his head blown off. I think it’s Miss Shoulter’s brother.’

If Mr Chickle had seemed angry before he was much more so now.

‘Miss Shoulter’s brother! What makes you think that, young man?’

‘It’s got his coat on,’ said Jack Ribbon lamely.

Mr Chickle seemed to have recovered himself.

‘Well, really, Ribbon, I don’t see why you should come and wake us up at this time of night. I was asleep and I expect Mrs Pluck was just going to bed. If as you say you’ve found some evidence of an accident, surely you should know that it’s your duty to report it to the police. Not to come ringing our door-bell.’

‘Yes, sir. I was a bit upset….’

Then Mr Chickle became more like his old self.

‘I must say you look upset, Ribbon. I’m sure it was very distressing. And since you are here and Mrs Pluck has not retired, you’d better drink something before you go to find the police. Give him a drop of brandy, Mrs Pluck.’

‘Thank you, sir. I didn’t ought to wait really. I ought to tell the police. It was a horrid sight, really it was. No head to speak of left, you might say.’

Mrs Pluck brought some brandy in a medicine glass, as though she wanted to stress the fact that it was restorative and not festive. Jack swallowed it.

Mr Chickle did not seem at all interested in the ‘horrid sight’. He asked no questions at all, and when the brandy was finished told Jack to hurry down to the village.

‘I expect you’ll find Constable Watts-Dunton in bed,’ he said. ‘But you should knock him up in view of what you have found. Please tell him not to disturb me again to-night, however. He will know what arrangements to make.’

Jack, feeling a little better, hurried on to the village and knocked at the constable’s door. It was ten minutes before he got any answer and then a woman’s head appeared at an upper window.

‘Yes?’ said Mrs Watts-Dunton.

‘Tell the constable there’s a dead man in Deadman’s Wood,’ said Jack breathlessly.

‘I’ll tell the constable,’ suddenly shouted his wife. ‘And you’ll see what happens to you, young Ribbon. He knows all about you and your silly larks. Now you’ve gone a bit too far, let me tell you. Waking people up …’

Jack began to lose his temper.

‘It’s true, I tell you. I’ve seen him myself. Half his head blown off.’

‘What d’you mean?’

‘You call the constable. There’s nothing funny about this. If you’d seen what I’ve seen.’

The window was closed, but after ten minutes Constable Watts-Dunton himself appeared at the door, fully clothed.

‘What’s this?’ he asked severely, as though Jack Ribbon was certainly to blame for something or other.

‘It’s what I say. A dead man in Deadman’s Wood.’

Constable Watts-Dunton, a thin and very solemn man who attended a chapel called Mount Sion and disapproved of most human activities, suddenly leant forward to sniff at Jack Ribbon’s breath.

‘Have you been drinking?’ he asked in a hollow voice.

‘I had a tot of brandy from Mr Chickle,’ admitted Jack. ‘I was upset, see? It’s not a nice thing to happen to anybody.’

‘What isn’t?’ asked Constable Watts-Dunton.

‘Finding a stiff in a wood with its head blown off.’

‘And what were you doing in the wood at this time?’ asked the constable.

‘On my way to church. Midnight Mass at Copling.’

‘No wonder,’ said Constable Watts-Dunton darkly, but did not enlarge on this cryptic negative.

‘I believe it’s Ron Shoulter,’ added Jack.

‘Oh, you do? Well, we’ll have to look into all that. You’d better come along and show me where you found whatever you have found. Wait a minute while I get my torch.’

So the police began their investigations rather earlier than Mr Chickle had anticipated.

CHAPTER EIGHT

It was Murder

WHEN Sergeant Beef and I arrived in Barnford it was New Year’s Eve, and the first rush of local excitement over the body found in Deadman’s Wood was beginning to subside.

We alighted at the station at about midday and Beef at once turned his mind to the question of our quarters. I have noticed on previous occasions that until he is what he calls ‘fixed up’ Beef will not begin to take any part in the investigations in hand.

‘Which is the best pub?’ he asked the ticket-collector.

‘Depends what for,’ the man said slowly. ‘The beer’s best at the Feathers, but there’s some nice people keeping the Crown. I should say the Feathers’ darts was better, but if you want a good warm fire in the bar the Crown’s the place. When it comes to company…’

At last Beef cut this short.

‘I want to put up for a few nights,’ he said.

‘Then you better try the Crown. The Feathers don’t do anything of that.’

‘How do I get there?’

‘Follow this road till you come to Potter’s the butchers, then turn right. It’s on your left.’

‘Thanks,’ said Beef, and picking up his suitcase marched off.

‘May as well be comfortable,’ he explained. ‘A nice little case like this should be enjoyable if we get decent quarters.’

I made no comment, though I could have pointed out the discrepancy between a corpse in a wood and ‘enjoyment’.

We found the Crown and Beef made for the Public Bar. Not until the beer in his pint glass had sunk by three or four inches did he approach the object for which we had presumably come to the inn.

‘Do you go in for accommodation?’ he asked the plump, middle-aged woman who had served us.

‘That depends,’ she said with a guarded look at Beef’s red face.

‘I was wanting to put up for a few days,’ explained Beef.

‘Commercial?’ asked the landlady.

‘Certainly not. I’m here to investigate the violent death of Mr Ronald Shoulter.’

He spoke in his most impressive accents. I could have kicked him for giving away our business.

‘Scotland Yard?’ asked the landlady with some animation.

Beef shook his head.

‘Private,’ he explained. ‘Representing the sister of the deceased. This gentleman’ – for the first time I was included in Beef’s negotiations – ‘is Mr Townsend, who writes up my cases.’

‘Well!’ said the landlady.

‘We could do with a couple of rooms,’ Beef continued.

I did not blame the landlady for hesitating. Beef being solemn and important was not an imposing sight.

‘I don’t think we should give you much trouble,’ I intervened with a smile.

The landlady still seemed dubious.

‘I’ll ask my husband,’ she said at last, and disappeared through a door behind the bar.

A few minutes later a little quick-spoken grey-haired sparrow of a man hurried in.

‘Bristling’s my name,’ he said. ‘Pleased to meet you. Detectives, eh?’

Beef cleared his throat.

‘Private investigators,’ he said.

‘On this job in Deadman’s Wood, I hear. Think it was murder?’

‘I have not yet commenced inquiries.’ said Beef loftily.

‘I see. Well, I don’t see why we shouldn’t put you up. Staying long?’

‘Difficult to say,’ said Beef. ‘Ve-ry difficult to say.’

‘Well, we’ll do what we can. Mother! Show them the rooms.’

‘I think we’ll have the other half first,’ said Beef. ‘What about you?’

When our glasses were refilled and Mr Bristling had his, Beef clumsily led the conversation to the matter in hand.

‘What’s thought about it in the village?’ he asked.

‘Well, we know the party

. The dead party, I mean. As a matter of fact I had to ask him to leave here one night. Caused trouble.’

‘What sort of trouble?’

‘Argument, leading to threats. He was fond of his liquor, see, and didn’t know when to stop. And when he’d had a few he got nasty. Very nasty, sometimes. That particular night he was arguing with Joe Bridge, a young farmer from Copling way.’

I became interested at once. With any luck this Bridge would be a suspect. I feel that in order to make Beef’s investigations interesting to the reader it is as well to have as many suspects as possible.

‘Has he a gun?’ I asked.

I could see that Beef did not like my quick-witted entry into the conversation. And I don’t think that Mr Bristling did, either.

‘Yes, Joe’s got a gun. What farmer hasn’t?’

‘You was telling us about Shoulter,’ said Beef.

‘Yes, he was a nuisance. Whenever he came down to stay with his sister he’d be round here or the Feathers drinking himself silly and quarrelsome. Owes me a bit of money, too.’

‘Think anyone had a grudge against him? A real grudge, I mean.’

‘Nobody liked him. But that’s not to say anyone ‘ud blow his brains out. Course, he was in with the people who live up in the wood-Flipps. That’s another one who likes his liquor. But he has it at home. Sends down for bottles when he can get them, and seems to get a bit from London. What there was between him and the Shoulters I don’t know.’

‘Ah!’said Beef.

‘Tell you what,’ said Mr Bristling. ‘There’s young Jack Ribbon who works for Miss Shoulter. He’ll know more. It was him found the body, too.’

Out came Beef’s enormous note-book, a relic of his days in the Force, and I saw him write in his laborious hand ‘J.Ribbon’ and underneath it, ‘J. Bridge’.

‘Then there’s the old gent that came to live here about a year ago. He might have heard something. Lives on the outside of the wood. Chickle, his name is.’

‘Initial?’

‘W.’

‘Thanks. That’s a start anyway.’

‘Inquest’s to-morrow.’

‘Been a long time over it, haven’t they?’

‘It’s been put off, I understand.’

‘Who’s in charge of the police investigation?’

‘An inspector from Ashley. Name of Chatto.’

‘Well, you’ve been very helpful.’

Mr Bristling had not finished yet.

‘There’s the constable here, of course. He’s not much use, except for hanging round at closing time. Proper spoil-sport he is. Chapel.’

‘What’s his name?’

‘Watts-Dunton.’

‘What?’

‘Watts-Dunton. With a hyphen.’

‘Gor’!’ said Beef. ‘I don’t know what the Force is coming to since I left it. Constables with hyphens. I once had a young constable called Galsworthy under me, and that was bad enough.’

‘There you are,’ said Mr Bristling. ‘And he’s a misery. Now what about lunch for you gents? I’m afraid there’s nothing much in. Still, we’ll see what the missus can do.’

It was not until nearly three o’clock that we left the Crown, and I was getting impatient.

‘No sense in hurrying,’ said Beef. ‘I’ve got to think,’

‘Whom do we see first?’ I asked.

‘We’ll do things correct,’ said Beef. ‘And call at the Police Station.’

This turned out to be the semi-detached house in which Constable Watts-Dunton lived. It was marked by a blue plate and a blue lamp. Beef marched up to the door and knocked boldly.

My first view of Constable Watts-Dunton confirmed the description given by Mr Bristling. He was a tall, cadaverous man who would have been in his element with a banner warning us that the Day of Judgement is at hand.

‘Well?’he asked.

‘I should like to see the inspector in charge of the Shoulter Case,’ said Beef.

‘Have you got any information for him?’ asked the constable with a mixture of gloom and self-importance.

‘Not yet. You tell him Sergeant Beef would like to see him.’

Watts-Dunton disappeared and returned to say that Inspector Chatto would spare him five minutes. We were shown into a little room in which there was a bright fire. At the table Inspector Chatto sat before a stack of papers. He was stout, clean-shaven, rather jovial, but I saw that he had quick, shrewd eyes.

‘You’ve heard of me?’ asked Beef rather anxiously.

‘‘Fraid not,’ said the inspector genially.

Beef turned on me almost savagely.

’There you are!’ he said. ‘Never heard of me. What did I tell you?’ Then, turning again to Inspector Chatto, he said: ‘Now if I was Lord Simon Plimsoll or Monsieur Amer Picon, or Mr Albert Campion, or one of them, you’d know of me quick enough, wouldn’t you?’

‘I’m not a great reader,’ said Inspector Chatto. ‘But I do know of these. Private detectives in novels, aren’t they?’

‘That’s right,’ said Beef. ‘And that’s what I am, or what I ought to be if Mr Townsend here was as good at his job as I am at mine. Five cases I’ve handled, inspector, and got the answer every time, though Inspector Stute himself will tell you…’

‘I know him, of course.’

I saw that it was time to interrupt.

‘Inspector,’ I said firmly, ‘my friend here talks a little impulsively at times. But what he says is substantially true. He is, in fact, a very clever investigator, and Inspector Stute will acknowledge his indebtedness to Beef on more than one occasion. I do trust you won’t be put off by my friend’s rather rough appearance and manner. I feel sure he can be of assistance to you. He is retained in this case by Miss Shoulter.’

Inspector Chatto lit a cigarette. He seemed rather amused.

‘I have no wish at all to discourage amateurs,’ he said. ‘And I’m quite prepared to believe that Sergeant Beef may be of assistance to us. But what exactly do you mean when you say that he is “retained” by Miss Shoulter?’

This was awkward. Beef had the sense to keep quiet and leave it to me.

‘Er – Miss Shoulter is under the impression that the police believe her brother’s death to be suicide. She is convinced that it is nothing of the sort. She wishes Sergeant Beef to collect any evidence there may be to that effect.’

Inspector Chatto was smiling openly now.

‘And if I tell you that the police are convinced of the same thing?’

‘You mean?’

‘I mean it was murder.’

There was an awkward silence.

‘In that case the only honourable thing for Sergeant Beef to do will be to tell Miss Shoulter that since the police are now convinced, there is no need for her to employ him.’

Inspector Chatto looked at both of us.

‘You were expecting to get a book out of this, Mr, er –’

‘Townsend. Yes, I did rather hope -’

‘Exacdy. Well, frankly I see no reason for the two of you to leave. It is an interesting little case. And at present I’ll tell you frankly we haven’t much in the way of a clue. Since you’ve come down here you may as well wait for the inquest.’

‘That’s very friendly of you, inspector.’

Beef nodded towards the stack of papers.

‘What about telling me what you’ve got?’ he asked crudely.

Inspector Chatto chuckled.

‘I see no objection,’ he said. ‘I should rather like to go over the case from the beginning. It might clear my ideas a bit. Watts-Dunton, d’you think your good lady could manage a cup of tea for us?’

Watts-Dunton’s face came as near to producing a smile as its gaunt features would allow it.

‘She’s got the kettle on now,’ he said.

‘Then let’s get down to it,’ said Chatto.

So in this amiable atmosphere, which Beef really owed to my ready apology for him and my explanation of his abilities, we were t

aken into the confidence of the police.

CHAPTER NINE

Police Confidences

‘WHAT you want to know, of course,’ began Inspector Chatto, ‘is what makes us think it was murder. That’s simple enough: The corpse was found with a length of red tape round his foot which was attached to the trigger of the gun. The inference being that he held the gun in an upright position, leaned over it and fired it with his foot. His head in that case could not have been more than eighteen inches at the most away from the gun. Now, if you care to read the medical evidence and the report of the ballistics expert you will find that in point of fact the gun was at least four yards, possibly more, from Shoulter when it was fired.’

Beef nodded knowingly.

‘That makes it murder,’ he said. ‘That’s good. I do hate suicide. Nasty panicky little crime. What else did the experts have to say?’

‘Not a great deal. The doctor did not see the body until early on Christmas morning. He could not say more than that the man had been dead for anything from nine to sixteen hours, that is to say that Shoulter was killed between one p.m. and eight o’clock on Christmas Eve.’

‘Not very helpful.’

‘The bullet man was better. You can be pretty accurate when it’s a shot-gun. The spread of the shot and so on. He believes that Shoulter was coming up the path, that is to say walking from Barnford towards Copling. That would be his quickest way from Barnford to his sister’s bungalow. The man who shot him was hidden on the wood side of a little clearing beside the path. You can see the place. There’s a fallen tree there which would make excellent cover. When Shoulter was about level with the murderer he probably looked towards him, because he got both barrels in his face. His distance in that case would be just four yards. Then the murderer must have rigged the thing to look like suicide. He had some red tape in his pocket and tied it round the barrel and made a loop for the man’s foot. Then he dragged the corpse across the clearing and dumped it behind the tree. There was evidence of the body being dragged across the wet, sticky ground.’

‘Did you see that yourself?’ asked Beef.

‘Yes. Constable Watts-Dunton here had the sense to get me out at once, though it was Christmas Day. When I came to have a look at the place I found everything untouched since the crime, except just for the footprints of young Jack Ribbon who found the body at eleven-thirty on Christmas Eve. It was very useful. There was no doubt about the body having been dragged across the clearing, though very determined efforts had been made to destroy the marks of dragging.’

Nothing Like Blood

Nothing Like Blood Death of a Bovver Boy

Death of a Bovver Boy Jack on the Gallows Tree

Jack on the Gallows Tree Case with No Conclusion

Case with No Conclusion Case for Three Detectives

Case for Three Detectives Furious Old Women

Furious Old Women Death of a Commuter

Death of a Commuter Case with Ropes and Rings

Case with Ropes and Rings Dead Man’s Shoes

Dead Man’s Shoes Case with 4 Clowns

Case with 4 Clowns Death with Blue Ribbon

Death with Blue Ribbon Death in Albert Park

Death in Albert Park Die All, Die Merrily

Die All, Die Merrily Death in the Middle Watch

Death in the Middle Watch Death at St. Asprey’s School

Death at St. Asprey’s School Case for Sergeant Beef

Case for Sergeant Beef