- Home

- Bruce, Leo

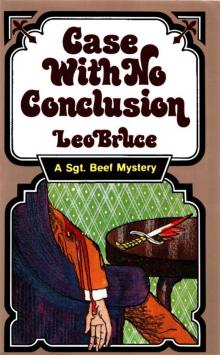

Case with No Conclusion

Case with No Conclusion Read online

Copyright © 1939 by Leo Bruce

Published in 1984 by

Academy Chicago, Publishers

425 N. Michigan Avenue

Chicago, IL 60611

Printed and bound in the U.S.A.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Bruce, Leo, 1903-1980.

Case with no conclusion.

Reprint. Originally published: London: G. Bles, 1939.

I. Title.

PR6005.R673C35 1984 823’.912 84-14556

ISBN 0-89733-117-6

ISBN 0-89733-118-4 (pbk.)

TO

BOB AND WINIFRED PARKER

Chapter I

I STARED gloomily at the piece of notepaper. Really there seemed no end to the ingenuous ambitions of my old friend Sergeant Beef. He had already hinted to me that he was thinking of retiring from his post as a country police sergeant, but I had never dreamed that the luck he had had in stumbling on the solutions to a couple of murder mysteries would lead him into anything of this sort. The notepaper was headed W. Beef, and underneath were these extraordinary words: “Investigations promptly executed. Estimates given. Secrecy, swiftness, security.” On the right of the paper was a London address, and on the left a telephone number.

Poor old Beef! A picture of him in his blue uniform at once rose to my mind. His straggling ginger moustache which always looked as though it had been dipped all too recently in beer, his irregular teeth and his air of mild remonstrance, his slow movements and his stolid way of thinking, marked him at once as the type of policeman likely soon to be superannuated by a Force full of zestful public-school boys. That he should have kept his job at Braxham had surprised me, for his fondness for the local pubs was a byword. That he should have been the means of tracing two murderers was a miracle. That he should be able to earn a living as a private investigator was beyond all human credulity.

However, there it was, and his letter followed. Written across his inferior notepaper in his large sprawling handwriting I read that he would like me to call on him as soon as possible. Concerned for his wife, a plain and sensible woman whose only ambition had ever been a clean cottage, plentiful meals and a gossip with her friends and relations, I decided to call at the address given.

I arrived there one afternoon at about half-past two, those doldrums of the day when lunch is finished and half-digested and it is not time for the reanimating cup of tea. Mrs. Beef opened the door of one of those small, two-storied, black, brick-built houses that may still be found in unlikely back streets between Baker Street and Paddington. Children were playing down the road, and the little front doors and closely curtained windows marked this unmistakably as a street in which bus conductors, workmen, postmen, and perhaps shop-assistants, whose work was in the Edgware Road area, had been lucky to find a small house for themselves. It was the last place in the world to which anyone looking for a private detective would come, even in answer to an advertisement.

“Beef’ll be round in a minute,” said his wife. “They close at half-past two,” she added significantly as she showed me into the small front room.

Here her own tastes were predominant—lace curtains, Victorian furniture, heavily framed photographs, and Goss china.

“How is he getting on?” I asked.

“Oh, well,” said Mrs. Beef, “it may give him something to do now he’s retired. He’s got a bit put by anyway, you know, and I don’t see it does anyone any harm for him to call himself a private investigator. Though what he wants to get mixed up in murders for I don’t know. I don’t mind reading about them in the papers. But further than that I won’t go.”

“Has he had any cases yet?” I asked.

“Cases? No,” said Mrs. Beef. “‘Course he hasn’t. But he’s started spending money putting advertisements in papers and says something’ll come along soon. I can’t help thinking you’re to blame, Mr. Townsend, writing up those other two affairs as you did into books. It’s given him such an idea of himself. Though I told him you were laughing at him half the time.”

“What we’ve got to remember,” I said, smiling, “is that he did actually discover the murderer in each case.”

“Oh, well…” said Mrs. Beef finally, “there you are. You never know. It’s a funny business….”

“Quite,” I interrupted, before she should reflect that life was what you make it, or that you never could tell.

Just then the front door opened and in a moment Beef was with us. I had never seen him out of uniform before, for in the old days he had preferred his blue tunic which, he said, he was “used to, for playing darts.” The sight of his bright blue serge suit and mauvish tie rather embarrassed me. He held out his big red hand.

“Glad to see you,” he said without smiling; “there’s several private things I want to talk about.”

This last remark was evidently his delicate and tactful way of suggesting that Mrs. Beef should leave us, for she immediately walked out of the room.

“Beef,” I began at once, “what on earth is the meaning of all this? Do you really suppose that you can make a private detective of yourself?”

“Make?” he said, “I’m a born detective. And you should know it if no one else doesn’t. I remember that time when the milk was disappearing off the doorsteps soon after I’d started in the Force. The Superintendent said to me then that I was a regular sleuth. A regular sleuth, he said, and no mistake about it.”

I sighed, for the old boy’s vanity made him invulnerable to sarcasm or contradiction.

“But what about your cases?” I asked; “Mrs. Beef says that you’ve been spending money on advertisements and nothing’s come to hand. How do you account for that?”

Beef sat down heavily in a plush armchair, pulled out his pipe and turned to me.

“That’s just what I wanted to see you about,” he said; “I don’t mean to say nothing rude, but I can’t help thinking that if anyone’s to blame, it’s you.”

“Me?” I began indignantly, but he held up his hand.

“Yes,” he said, “the way you wrote up those cases. It was almost as though you were trying to make a fool of me. I got the murderers, didn’t I? What more do you want?”

“But, Beef,” I said, “you know you were lucky…”

“There’s no such thing as luck in this work,” said Beef. “Didn’t Stute say so himself when he came down from Scotland Yard? It’s method, Mr. Townsend. My methods are simple, but they work. I don’t believe in a lot of skylarking about with microscopes and using half the inventions of Scotland Yard to sort out a little bit of evidence what anyone could see through with half an eye in their head. And there it is. I’ve arrested these two, and all I got from you was remarks about my being a simple country policeman. Then the way you put my language into print won’t do neither.”

“But after all, Beef,” I said, “I only reproduce your dialect as accurately as possible. You’re not a true Cockney, and I went so far as to explain that you spoke as Cockneys spoke in the home counties.”

“Dialect,” said Beef disgustedly; “it’s nothing short of personal the way you have it printed. You should read the newspaper critics. You saw what Mr. Milward Kennedy said. ‘Tedious’ he called it, the misspelling and that.”

“If ever you have another case,” I assured him, “and I have to report it, I promise you your language will go in with all its aspirates, and none misplaced.”

“I’m not sure you’re the one to report it,” said Beef. “You don’t seem to make much of my cases. Not what some of them do for their detectives. Case Without a Corpse never hardly got no notices at

all in the newspapers. Not like Miss Christie, or Mr. Freeman Wills Croft. They do get taken notice of. All you got for me was a bit in the Sunday Times, and not a smell from the Observer. A couple of paragraphs in highbrow papers like the Spectator and The Times, and there you are.”

“I don’t know whether that’s quite fair,” I said. “What about Raymond Postgate in Time and Tide? He called me the ‘thriller reviewer’s comforter.’ ”

“Only because you try and sneer at the others as writes detective stories what sells hundreds of thousands more than whatever you will. Why can’t you make me famous? Like Lord Simon Plimsoll and those. I’m just as sure to get the right man in the end, aren’t I? See where it comes in when a real good case comes along what really might help me to build up a connection, I don’t get it. ‘Course I know the competition’s there. There’s hundreds of them after anything unusual. There was that nice little case the other day, for instance, that would just have suited me. Body found in a brewer’s vat. And who got the job? Nigel Strange-ways, of course, Nicholas Blake’s detective. And what about that kidnapping business down at Kensington? It would have been handy for me, but Anthony Gethryn was put on to that because he’s got Mr. Philip Macdonald to write him up. Where were we, I’d like to know? Then again, what about Fashion in Shrouds? Lovely, that was. Murder in a fashionable dress-designer’s in Mayfair….”

“But, Beef, surely you’re not going to suggest that you would have been the man to investigate that case? It needed delicacy, tact, savoir faire. It was obviously just right for Miss Margery Allingham’s Albert Campion.”

“But I shouldn’t half have liked it,” said Beef, “mannequins and that,” and he gave me a gross wink. “I never have any fun. Doctor Gideon Fell got that interesting little business of the two corpses in a hotel, with John Dickson Carr to tell the story. Why, even my cousin does better than I do.”

“Your cousin?” I asked.

“Oh, you didn’t know there was another Sergeant Beef? Of course, he’s only an assistant to John Meredith, but he gets some interesting cases too. And you know why? Because Francis G6rard writes them up, and not someone like you who’s only thinking how he can make jokes at my expense. Yes, my cousin Matthew Beef was telling me the other day, ‘William,’ he said, ‘what you want is a first-rate man to write your stories, like Mr. Gerard does ours. That Townsend’s no good,’ he said, ‘he’s trying to be clever half of the time.’ You see what’s being thought.”

I coughed uncomfortably.

“No, it all comes down to the same thing: I’m wasting my time. I need someone who can show I’ve got brilliance, insight, intuition, psychology, and all those remarkable things the others are supposed to have—though they don’t work out anything more difficult than I do. It’s disheartening, that’s what it is.”

“I’m sorry, Sergeant,” I said, because I couldn’t really be angry at this absurd tirade. “If ever you should get another case we must see what we can do.”

“Of course, I shall get another case,” said Beef. “What do you think I’ve put advertisements in the papers for and my name on that door? Don’t you know what happens? A mysterious stranger comes up, hot and perspiring with anxiety, tells me his wife’s disappeared, and Bob’s your uncle. You ought to know.”

“Well, let’s hope it does happen,” I returned.

“Though I don’t know,” added Beef, with heavy jocularity, “that I should be in a hurry to trace her. I should be more inclined to congratulate him, and leave it at that.”

Chapter II

IT must have been a fortnight later when I received a ’phone call from the Sergeant saying that Mr. Peter Ferrers was due to come and see him at four o’clock that day.

“It’s this Sydenham case,” he added breathlessly; “his brother’s charged with murder and he’s come to me to clear him. What do you say to that?”

I said nothing very much, except to congratulate Beef on the opportunity, and to promise that I would join him in Lilac Crescent at three-thirty.

As I sat with him waiting I didn’t much like the way that the case was already following the precedents. Here we were not five hundred yards from Baker Street expecting the inevitable ring. And when Mrs. Beef put her head in the door to say that our first customer was looking at the numbers outside, I felt no particular excitement.

“Customer,” roared Beef, as his wife went out to the passage; “she ought to know better than that. Client’s the word.”

But the young man who was shown in would have been the first to disclaim the pretentiousness of that title. He was perhaps twenty-eight years old, slim and fair, with an open intelligent face, and dressed inconspicuously. I was glad to see none of the inconsequential regalia that young men so often carry—badges in buttonholes, ties of some immensely significant design, shirts of some knowing colour, all implying that they belong to this school or that movement. Beef eyed him appraisingly, and his first words surprised me.

“I’ve met you before, sir,” he said pleasantly.

“Really?” said the young man. “I don’t remember it.”

“Ah, but you will when I tell you,” replied Beef, his face spreading into a good-natured smile. “Don’t you remember that Darts Championship when you and another young fellow played me and George Watson in the semi-finals? I finished on a hundred and twenty-seven that night. Treble nineteen, double top, and double fifteen. Nice get-out, that was.”

Mr. Peter Ferrers nodded amicably. “Oh yes,” he said, “I do remember now.”

“Still,” said Beef, with an air of coming to business, “you didn’t come here to talk about darts, did you? What can I do for you?”

“Briefly,” said the young man, “you can save my brother from being hanged for the murder of Doctor Benson, which he certainly didn’t commit.”

“Ah,” said Beef, pronouncing that non-committal monosyllable as though he knew all, but would say nothing at this point.

“Perhaps you have read the case,” went on young Ferrers. “The papers have already given it a title—the Sydenham Murder, it’s called.”

“I don’t hardly think it’s fair, the way they make stories out of real murders, do you, sir? It’s poaching on the detective novelist’s department, I think. Torso Mystery, Burning Car Case and that.”

I was beginning to feel uncomfortable, and wondered what young Ferrers could think of Beef. However, the latter had pulled out the enormous notebook which had followed him from his police-force days, and prepared to take down the details.

“My brother lived in Sydenham,” said young Ferrers, “in a house called the Cypresses; one of those big gloomy mansions built for rich Victorian city men. We were both brought up there. When my father died a couple of years ago my brother decided to stay on. I believe he had an offer for the site from a Building Society—I could never understand his not accepting it. For in spite of our associations with the place it was inconvenient, cold, and cheerless. However, he’s a bit of a sentimentalist and wouldn’t leave the home. On Thursday night, a fortnight ago today, he gave a small bachelor party to which he invited Doctor Benson, who had been our family doctor for years. He didn’t actually bring us into the world, being a man of forty-five himself, but since he had set up his plate in Sydenham fifteen or twenty years ago he had attended my father and us. I should perhaps explain the relationship because I think it’s an unusual one. I never very much cared for Benson, finding him intolerant, and of a brusque, almost brutal disposition. He had a small gymnasium at the back of his house, and I remember that when we were boys, he persuaded my father to send us round to spar with him, and I think he took pleasure in knocking us about. But he kept my father’s confidence, and that, I suppose, accounts for my brother’s keeping up the friendship.”

“What about his wife?” broke in Beef suddenly and rather rudely. It was evident that he had read newspaper accounts of the case.

Young Ferrers looked up, and for the first time I noticed some emotion in his face, though I coul

dn’t altogether define it.

“Mrs. Benson,” he said slowly, “is a very handsome and a very charming woman. Benson married her five years ago, and it seems that the police pay great attention to the fact that my brother was supposed to have been his rival at the time. I should prefer to say no more about this. You can meet the lady yourself, and if she is prepared to answer questions, you can ask them.”

There was a moment’s silence, and then Peter Ferrers continued: “The other guests at dinner were Brian Wakefield, who is a friend and colleague of mine, and myself. I had been trying for some time to interest my brother in the paper I run, and had wanted him to meet Wakefield, who is my fellow-editor.”

“What paper’s that?” I asked.

“It’s called the Passing Moment,” said young Ferrers.

“Do you put bits about books in it?” asked Beef at once. “Because I don’t remember reading nothing about either of my cases in a paper with that name to it.”

“I’m afraid we’re chiefly concerned with politics,” said young Ferrers mildly.

“What kind of politics?”

“Oh, vaguely towards the Left,” Peter Ferrers told him.

Beef nodded. “That means you’re a bit on the Socialist side, then?” he said. “Well, I voted Labour myself last election. I mean, I wouldn’t like to see nothing like what’s going on in Russia in this country, but I couldn’t stand one of these jumped-up dictators, holding his hand out as though he had something in it what he wanted to keep away from his nostrils.”

And with that summary of his political views Beef seemed satisfied. I, on the other hand, examined young Ferrers with a new, and not altogether sympathetic, interest. I disapproved of his type, which, however idealistic, seemed to me to be a disturbing element. But I could see that Beef liked him.

“Perhaps,” said Peter Ferrers calmly, “we had better return to the matter I came to discuss. We dined at eight, and at half-past nine I and Wakefield left. He lives in a little flat in Blackfriars—three rooms, which I told him might be offices, but which he has converted into quite pleasant living quarters, and claims that they are quiet at night and perfectly convenient. I then drove on to the big block of service flats near the Marble Arch, in which I live, reaching there, I suppose, at about half-past ten.”

Nothing Like Blood

Nothing Like Blood Death of a Bovver Boy

Death of a Bovver Boy Jack on the Gallows Tree

Jack on the Gallows Tree Case with No Conclusion

Case with No Conclusion Case for Three Detectives

Case for Three Detectives Furious Old Women

Furious Old Women Death of a Commuter

Death of a Commuter Case with Ropes and Rings

Case with Ropes and Rings Dead Man’s Shoes

Dead Man’s Shoes Case with 4 Clowns

Case with 4 Clowns Death with Blue Ribbon

Death with Blue Ribbon Death in Albert Park

Death in Albert Park Die All, Die Merrily

Die All, Die Merrily Death in the Middle Watch

Death in the Middle Watch Death at St. Asprey’s School

Death at St. Asprey’s School Case for Sergeant Beef

Case for Sergeant Beef