- Home

- Bruce, Leo

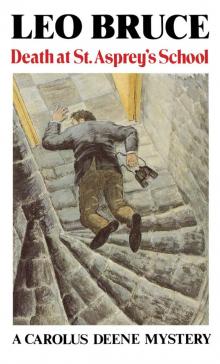

Death at St. Asprey’s School

Death at St. Asprey’s School Read online

Death at St. Asprey’s School

In this new Carolus Deene story, set in a boys’ prep, school, it is very much a case of blackmail amongst the blackboards, of mayhem and murder, where Carolus is called in to investigate a series of spooky happenings at St. Asprey’s. But the ghostly charades are only a prelude to murder, and a fight to the death for Carolus.

Written tautly, and with delightful understanding of schoolboy love and language—and the ennui of the teachers in the suffocatingly tense atmosphere of the school—this is an exciting detective story.

© Copyright 1967 by Leo Bruce

First American Publication 1984

Academy Chicago, Publishers

425 N. Michigan Avenue

Chicago, Illinois 60611

Printed and bound in the U.S.A.

Second printing, 1987

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Bruce, Leo, 1903-1980.

Death at St. Asprey’s School.

Reprint. Originally published: London: W.H. Allen, 1967.

I. Title.

PR6005.R673D39 1984 823’.912 84-388

ISBN 0-89733-095-1

ISBN 0-89733-094-3 (pbk.)

Chapter One

On an airless June night the boys in a dormitory of St. Asprey’s Preparatory School were disturbed when one of them, a certain Maitland, had a violent fit of hysterics. Normally a dull if not lethargic boy, he seemed now to have entirely lost control of himself as he shrieked and pointed to the window.

One of the boys immediately ran for Matron, and a skinny woman with prominent teeth appeared, wrapped in a workmanlike dressing-gown. Slapping Maitland sharply across the face she reduced him to gloomy but less hysterical tears and the remaining boys to silence.

“Whatever’s the matter with you?” she asked the snuffling Maitland, the son of a prominent ecclesiastic.

“I saw something,” said Maitland desperately.

Curiosity, a constant and lively emotion in Matron, came to the fore. There had been so many ugly and frightening events at the school lately that she was prepared for almost any revelation.

“Well, what?” she asked impatiently.

“Af… face,” blubbered Maitland.

This had implications for Matron.

“Where?” she asked.

“At the window.”

The dormitory was on the first floor. Matron began to hope that the boy was suffering from delusions.

“What kind of face?”

“A man’s.”

“Someone you knew?”

Maitland shook his head.

“It was a beastly sort of face,” he said.

“It’s gone now,” Matron pointed out. “You’d all better get to sleep or I shall have to call Mr. Sconer.”

Just as she reached the door, Maitland shouted wildly—“Don’t turn the lights out, Matron!”

Even the bravest warrior may realize when the odds against him are too high and Matron saw that the situation had gone beyond her authority.

“Whatever’s the matter with you?” she asked, but she left the lights on while she went to call for help.

This came in the person of the headmaster’s wife, a formidable woman named Muriel Sconer who, through some association of ideas among the boys, was known as Mrs. Bun. Unlike Matron who had rushed to the dormitory at the first summons, Mrs. Bun had given some moments to her appearance and approached in a magnificent peignoir.

“What’s the matter, Matron?” she asked with lofty confidence in her own ability to deal coolly with any crisis.

“It’s Maitland, Mrs. Sconer,” Matron said. “He’s been having a nightmare, I think. I found him quite hysterical, saying he saw a face at the window.”

“Nonsense,” said Mrs. Sconer sharply.

“He does not want the light out,” Matron exclaimed.

“Now, boys,” called Mrs. Sconer in her rich contralto voice, “you must all go to sleep and stop all this silliness. I’m surprised at you, Maitland. I thought you were more sensible.”

“Please, Mrs. Sconer, I did see it.”

“Another word from you and you’ll Go To The Study tomorrow,” said Mrs. Sconer peremptorily. This produced silence, as might be anticipated, but not acquiescence in the extinguishing of lights.

“Please don’t turn the light out, Mrs. Sconer.” cried Maitland desperately.

“You’d better go to Matron’s room and get a pill,” was Mrs. Sconer’s lofty rejoinder. “Give him an aspirin,” she whispered to Matron. “You must have been dreaming. Now off to sleep, the lot of you.”

Returning to her room, however, Mrs. Sconer was far less calm than she appeared. The events of that term were enough to disturb anyone, even this monumental woman who dominated her world so arrogantly. Only a week ago there had been a scare in the Senior Dormitory when all the boys, serious youngsters of twelve and thirteen years, swore to having seen what they variously called the Monk, the Old Friar or the Abbot. Their accounts of this phenomenon tallied and could not be shaken even under the threat of Mr. Sconer’s cane. A ‘man in grey like you saw in books’ bearded, pale and tonsured, had passed through the dormitory ‘mumbling Latin’. A ghost? Oddly enough they did not think it was a ghost. It seemed more real. A joke? No, they said, they were sure it wasn’t a joke. It remained a mystery, but what seemed certain to the adults was that someone was deliberately disturbing the life of the school with these manifestations.

But such phenomena, unpleasant as they were and productive of anxious letters from parents, were not the worst influences over the once placid life of the school. Something hostile and corruptive was at work and everyone’s nerves were on end. Tempers in the common-room were frayed and there had been a number of senseless outbreaks over trivialities. The happy and jocular relationships which had once been noticeable amongst the staff, when even Matron had been known to smile cautiously at the latest classroom anecdote, had turned to suspicion and secretiveness and Matron herself, so long believed to be a mere ‘sneak’, a laughable bearer of news to Mrs. Sconer, had become an almost satanic figure, a centre of malignant intrigue. Everywhere was tension, anxiety, distrust as though some tragic event was impending.

The actual events which were held responsible for this might not in themselves be thought world-shaking, but they seemed to have some occult significance to the overwrought nerves of the proprietors and staff of St. Asprey’s. Footsteps had been heard in the passages at night, not the patter of boys’ feet, but the measured pacing of a man, yet those who had been rash enough to open their doors had seen nobody. Lights, spoken of as ‘lanterns’ had been seen moving about the grounds when all Christian folk should have been sleeping.

When six Angora rabbits belonging to a boy called Charlesworth had been found one morning dead in their hutch, their skulls battered, it had aroused furious indignation and much sympathy for the owner, but no explanation for the crime had been found. The boys began to talk of Dracula and other creatures found in horror comics, and a stern censorship had to be exercised over Sunday letters. ‘Dear Mother and Father, Last night we saw a gost’ was no matter for laughter in a school which depended on parents’ satisfaction with the education and living conditions for which they were paying high fees, and ‘Dear Mother and Father, On Friday all Charlesworth’s rabbits were slain by a Vampire’, had to be erased and a new sheet of notepaper issued to the correspondent.

At long secret conferences Mr. and Mrs. Sconer, the proprietors of the school, discussed these matters, realizing their seriousness.

“What will happen on Sports Day I

daren’t think,” said Mrs. Sconer. “The parents will hear the most grossly exaggerated stories. I shouldn’t be surprised if we lose a dozen boys. You really must do something, Cosmo.”

Her husband was a gaunt muscular man, rather ineffectual she had always thought, and usually respectful of her wishes.

“I don’t see what is to be done,” he said. “I’ve forbidden all pets after this term. We can’t have them sending the creatures home now. In many cases the parents would not know how to feed them and would be most indignant at receiving a litter of guinea-pigs.”

“Then get rid of Sime,” said Mrs. Sconer.

Colin Sime was one of the assistant masters, a clever teacher according to Mr. Sconer and among the boys ‘the most popular master in the school’, but disliked by the staff and detested by Mrs. Sconer.

“I don’t see how I can do that, my dear,” said Mr. Sconer miserably. “Unless we have evidence that he is somehow involved in all this.”

“Of course he is!” said Mrs. Sconer. “Anyone can see it. I’ve always told you that he’s shifty and undesirable.”

“But he’s an excellent teacher. He gets the boys through the Common Entrance exam.”

“There won’t be any boys to be got through it very soon if things go on like this. That young man you’ve just taken on…

“Mayring?”

“Yes. He was disgracefully rude to Matron yesterday. You will please tell him, Cosmo. Matron is quite irreplaceable, as I’ve told you before.”

“She’s not popular with the Men,” said Mr. Sconer.

He was not voicing a wide generalization. ‘The Men’ were the assistant masters.

“I should think not. She’s far too loyal to me for that. But I won’t have that overdressed youth insulting her.”

“Mayring is a first-rate cricket coach, my dear, and Parker is getting past it.”

“Parker!” snapped Mrs. Sconer contemptuously. ‘Jumbo’ Parker was that faithful old assistant who had been at the school for twenty years and had no other home or interest—a type common to almost all English preparatory schools. Sconer said nothing when his wife brought out his name in that tone, though it was known that he depended on Parker in many ways. “The only man you’ve got who is at all worth his salary is Jim Stanley.”

“He’s not much of a disciplinarian,” Sconer pointed out, making a notable under-statement.

“But he’s a gentleman, which is more than you can say for the rest of them,” his wife told him triumphantly. “As for Sime…”

Somewhat feebly Mr. Sconer pleaded urgent work. He did not want his wife’s opinion on Sime, which he knew too well, to be repeated.

But in the days following the incident of ‘the face at the window’, the staff of St. Asprey’s School, till then merely startled and worried by curious happenings, began to realize that there was something more sinister at work than a nocturnal practical joker and felt the first real pangs of fear. Once loosed in a small, fairly isolated community like this. fear could grow and turn to terror, and this is what happened.

Its first serious manifestation came on the very next morning and was generally connected with that apparition. Young Arthur Mayring, who last term had been still at his public school, Radley or was it Uppingham? had obtained the headmaster’s permission to bring back to the school a fox terrier puppy named Spike which he kept in the stables. The little creature was well-behaved and though Matron had blamed it for the presence of a flea in Stewart II’s underpants, no one had ever had cause to complain that Spike was noisy or a nuisance.

Young Mayring had gone as usual to the stable after breakfast and found that his pet’s throat had been cut and the puppy was lying dead in a pool of blood. A more experienced Man would have kept knowledge of this from the Boys, but Mayring was so badly shaken by his discovery, so furiously angry and so heartbroken that he confided in the first persons he met who happened to be Richardson and Plumber, two twelve-year-olds. Before morning school began there was not a pupil at St. Asprey’s unaware that Mr. Mayring’s dog had been foully murdered, and gory details ran from mouth-to-mouth.

It was the pool of blood that seemed to appeal to the common imagination and Mrs. Sconer lost her head a little when she heard of it.

“It’s ruin,” she said to her husband. “With Sports Day next week.”

Not the Hartnell dress in which she had invested for the occasion, not all her crocodile charm with the parents would pacify their anxieties when they heard from their sons of the blood lust and horror abroad in the school. “You should never have engaged Mayring and certainly never allowed him to import livestock.”

“My dear, I was scarcely to know…”

“I have warned you, Cosmo. Perhaps now you will give Sime notice.”

“But what has Sime to do with this?”

“That is for you to find out. I am convinced he is in some way responsible.”

“It seems to me like the work of a maniac.”

“It is. And how do you know that it is not that of a homicidal one?”

“My dear … a dog…”

“The species is no proof. Next time it may be far worse.”

“Really, Muriel. You speak as though we had to anticipate murder in the school.”

“I should not be in the least surprised. Perhaps then you will realize that my advice should have been taken months ago.”

“But murder…”

“It’s no use your repeating the word, Cosmo. Matron believes her tea was tampered with the other day. She has her suspicions that someone it trying to poison her.”

Mr. Sconer may inwardly have been crying ‘good luck to him!’ but his face continued to be sad and anxious.

“She must surely be exaggerating,” he said. ‘Matron says’ was not his favourite phrase when it was spoken by his wife.

“She is a shrewd and competent person. I am thankful to have someone I can rely on in the school.”

In the common-room that day not much was said, though at first there was sympathy for Mayring. His threats, however, of what he would do to his dog’s assassin if he found him grew tiresome as the day went on and received no encouragement from the other Men who remained sullen and taut, resolving to lock their doors that night.

Richard Duckmore, the fourth of the five assistant masters, who was always a highly-strung individual, showed signs of overstrain. His hands were unsteady and the twitch which always afflicted him grew more noticeable.

Two nights later the school was again aroused by piercing screams, this time from Matron herself. Mrs. Sconer hurried to her room and found her ally gibbering with disgust and horror as she pointed to her turned-back bed on which a dead rat was incongruously lying.

“I put my foot on it!” she yelled, her eyes staring wildly at the headmaster’s wife.

“Some idiotic joke,” suggested Mrs. Sconer.

“Joke! You call that a joke? I shall never be able to get into bed again. I could feel the fur!” went on Matron hysterically.

“Most unpleasant. Whoever did this shall be punished—I promise you that. If it is one of the Men he shall be dismissed instantly.”

Matron had not yet pulled a dressing-gown over her sensible night gown and Mrs. Sconer could not help noticing that without reinforcement Matron’s hair was inadequate to conceal her incipient baldness.

“I could not possibly sleep here,” Matron warned her.

“The thing must be removed,” said Mrs. Sconer majestically. “Wait—I’ll call Parker.”

In a few moments ‘Jumbo’ Parker, looking somewhat puffy and crimson, had picked up the corpse with a newspaper and carried it away. When a senior boy named Chavanne appeared from his dormitory Mrs. Sconer, forgetful for the first time that the boy’s father was a millionaire with three younger sons to educate, spoke sharply.

“Back to bed this instant,” she said.

“Please, Mrs. Sconer, I heard someone screaming.”

“You heard nothing of the sort. Chavann

e, unless you want to Go To The Study tomorrow.”

Chavanne knew the emptiness of this threat.

“I thought the Vampire had struck again,” he said.

“Don’t be ridiculous. Matron was not feeling well. Now back you go to bed and don’t talk a lot of nonsense to the other boys.” Chavanne departed wondering and Mrs. Sconer continued to Matron—“You see what happens?”

Matron felt this was an implied reproach.

“I shall have to leave,” she said. “I can’t stand any more of this sort of thing.”

“We’ll talk about that in the morning,” said Mrs. Sconer, sounding friendlier, as she prepared to return to her room.

The habit of years impelled Matron, even in this crisis, to confide her latest discovery.

“Jim Stanley and the Westerly girl went out together again this afternoon,” she said.

‘The Westerly girl’ was Mollie Westerly, teacher of the most junior class, a pretty young person believed to be an heiress who had joined the staff that term.

“They did?”

“I saw them leave. Then Sime was up on the church tower again with the field glasses from the rifle range.”

“You are sure?”

“Positive. I know he’s watching them.”

“It’s all very disturbing, Matron. You had better sleep in the little spare room for tonight.”

“Yes,” said Matron. “I don’t think I could sleep here again.”

This was less positive than Matron’s last refusal, but still argued her position. She had never liked her bedroom, and was determined to change it. Mrs. Sconer, however, had no intention of permitting the change.

“I don’t wonder,” she said with a benign smile. “It must have been horrid for you. We shall have to see that this room gets a good old turn-out tomorrow and a change of sheets and blankets.”

“I don’t know whether…”

“Good night, Matron,” said Mrs. Sconer and with a speed remarkable in a woman so statuesque was gone.

She found her husband anxious and irritable.

“What wash that infernal noish?” he asked thickly for he had not put in his teeth.

“It was Matron,” said Mrs. Sconer.

Nothing Like Blood

Nothing Like Blood Death of a Bovver Boy

Death of a Bovver Boy Jack on the Gallows Tree

Jack on the Gallows Tree Case with No Conclusion

Case with No Conclusion Case for Three Detectives

Case for Three Detectives Furious Old Women

Furious Old Women Death of a Commuter

Death of a Commuter Case with Ropes and Rings

Case with Ropes and Rings Dead Man’s Shoes

Dead Man’s Shoes Case with 4 Clowns

Case with 4 Clowns Death with Blue Ribbon

Death with Blue Ribbon Death in Albert Park

Death in Albert Park Die All, Die Merrily

Die All, Die Merrily Death in the Middle Watch

Death in the Middle Watch Death at St. Asprey’s School

Death at St. Asprey’s School Case for Sergeant Beef

Case for Sergeant Beef