- Home

- Bruce, Leo

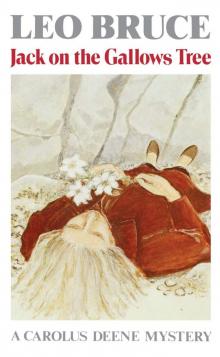

Jack on the Gallows Tree

Jack on the Gallows Tree Read online

Jack on the Gallows Tree

WITHIN the space of an hour or two the dead bodies of two elderly ladies, Miss Sophia Carew and Mrs. Westmacott, were discovered in the vicinity of the town of Buddington-on-the-Hill; both women had been very recently murdered; death in each case had been caused by strangulation; each was found lying at full length clasping in her hands the stem of a Madonna lily. As far as anyone knew there was no connection between the two women; they had never met each other; although both were well-to-do there was no evidence that a beneficiary from the will of one could expect any benefit from the will of the other.

The work of a maniac? Could there be two murderers planning together their foul deeds? It falls to Carolus Deene, the inimitable schoolmaster—who was supposed to be taking it easy, recuperating from a severe attack of jaundice—to unravel the knot of mystery and prove himself once again a master detective.

By the Same Author:

“SERGEANT BEEF” NOVELS:

Case for Three Detectives

Case without a Corpse

Case with No Conclusion

Case with Four Clowns

Case with Ropes and Rings

Case for Sergeant Beef

Cold Blood

“CAROLUS DEENE” NOVELS:

At Death’s Door

Death of Cold

Death for a Ducat

Dead Man’s Shoes

A Louse for the Hangman

Our Jubilee is Death

Furious Old Women

A Bone and a Hank of Hair

Die All, Die Merrily

Nothing Like Blood

Such is Death

CAROLUS DEENE “DEATH” NOVELS:

Death in Albert Park

Death at Hallows End

Death on the Black Sands

Death at St. Asprey’s School

Death of a Commuter

Death on Romney Marsh

Death with Blue Ribbon

Copyright© 1960 Propertius Co.

First American Publication 1983

Second printing 1988

Published by

Academy Chicago Publishers

425 North Michigan Avenue

Chicago, Illinois 60611

Printed and bound in the USA.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bruce, Leo, 1903-1980.

Jack on the gallows tree.

I. Title.

PR6005.R673J3 1983 823′.912 83-3746

ISBN 0-89733-071-4

ISBN 0-89733-072-2

For three wild lads were we, brave boys,

And three wild lads were we;

Thou on the land, and I on the sand,

And Jack on the gallows tree!

SIR WALTER SCOTT

Guy Mannering

1

“Torquay Deaths: Man Questioned,” read out Mr Gorringer in a voice stern with disapproval.

“Drink your tea before it’s cold, dear,” said his wife. “I don’t know what you’re worrying about. There’s always something in the papers.”

Mr Gorringer, headmaster of the Queen’s School, New-minster, cleared his throat with an enduring and significant rumble.

“In the circumstances, my dear, I have every cause to worry. Every cause. All the acts of violence this morning seem to have taken place at seaside resorts.”

“Well?” said Mrs Gorringer, whom her husband considered a witty woman, though not, fortunately, at breakfast time.

“You are doubtless aware that my Senior History Master, Carolus Deene, is being sent by his medical adviser for a period of recuperation by the sea after a severe illness. Hm. Bournemouth Model Found Dead. Police Search for Man with Arm in Plaster. It’s a serious matter.”

“But surely, if Carolus is recovering from jaundice he won’t have time or energy to get mixed up in anything of that sort?”

Mr Gorringer set down his large teacup.

“In some years of experience of Deene, my dear, I have never known him in any circumstances to lack the energy or the time for his sordid hobby. If he finds himself within reach of a corpse—I speak figuratively, of course—he will become involved in details which are most unfitting in an assistant of mine here at Newminster. If he catches so much as a whiff of murder he will be on the scent with all the persistence and gusto of a dachshund in search of truffles.”

“Do dachshunds search for truffles?”

“I have always understood so. It explains their extraordinary shape, no doubt. Can you wonder at my anxiety? Scarborough Case: Woman Charged. It’s nothing short of disturbing.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Mrs Gorringer. “I don’t see it does much harm. It’s a hobby, like any other. It seems to bring the school’s name forward, if anything.”

Mr Gorringer addressed his wife as though she were the Board of Governors.

“I do not fail to realize that Deene’s book Who Killed William Rufus? And Other Mysteries of History enjoyed considerable popularity among readers of a certain class,” he said. “I am perfectly aware that his reputation extends beyond the confines of our academic backwater. I recognize that as a teacher he is both talented and assiduous. But I cannot for a moment accept the fact that these excursions of his into contemporary crime do anything but besmirch the fair name of the Queen’s School. It has come to my ears that even while on his sickbed in the school sanatorium he was engaged in reading a work called The Etiology of Delinquent and Criminal Behaviour by an American writer no doubt suitably named Walter C. Reckless. What am I to say to that? Now that he is to be sent to the seaside, I feel something very like alarm.”

“Why not get Dr Tom to suggest somewhere else? A resort in which they don’t murder one another?”

“It is not so easy as you imagine, my dear. These unfortunate cases seem positively to follow Deene. However, I will as you suggest have a word with Dr Thomas. It may be some retreat can be found from which Deene will find it hard to escape.”

Mr Gorringer rose and set his mortarboard firmly on his head so that his large red ears protruded over the lower part of it. He pulled on his gown and in a short while was crossing the school quadrangle at a swinging yet dignified pace.

On reaching his study he rang for the school porter, a disgruntled individual called Muggeridge, who resented his orders to wear a uniform that included a gold-braided silk hat.

“Yes?” sighed Muggeridge when he appeared. Mr Gorringer ignored this.

“Good morning, Muggeridge,” he said brightly but firmly. “I want a word with Dr Thomas.”

“He’s not here.”

“I am perfectly aware that Dr Thomas does not come to the school until eleven o’clock, Muggeridge. When he pays his call be so good as to ask him to see me, please.”

“If I can catch him I will. He dives in and out like a jack-in-the-box sometimes.”

“Just make a point of it,” said Mr Gorringer loftily.

The porter turned to go.

“Oh, by the way, Muggeridge. There is something I have frequently intended to ask you. What is your Christian name?”

“Mal …” began the porter.

“Don’t say it!” said Mr Gorringer in some alarm.

“Malachi, if you want to know. It’s not my fault and I told my father about it years ago. Saddling anyone with …”

“That will do, thank you, Muggeridge. You may go.”

At eleven o’clock the headmaster was again seated at his large desk, apparently absorbed in the papers before him. When the doctor entered he looked up and spoke affably.

“Ah, Thomas,” he said. “I wanted

a word with you. Pray take a seat. How is our friend Deene?”

“He’s all right,” said the doctor carelessly. “I’m packing him off in a day or two for a fortnight’s sea air.”

“It was that which I wished to discuss with you. After his unfortunate illness he is doubtless in a somewhat weak condition?”

“Oh, Carolus has a tough constitution. He will be fit as a flea in a week or ten days.”

“By which time our term will be finished. Where did you think of recommending him to go?”

“It doesn’t matter much, really, so long as he gets some good air. Torquay, perhaps. Scarborough. Bournemouth. Wherever he likes.”

The headmaster winced.

“I cannot help but feel,” he said, “that he would be better suited by one of the inland spas.”

“Oh. Why?”

“You are perhaps aware of his predilection for involving himself in criminology? It would surely be disastrous to his health if at this time when he so sorely needs rest he were to be brought in contact with something which would disturb his repose and retard his recovery?”

Dr Thomas smiled.

“I don’t know. He likes that sort of thing. It might do him a power of good.”

“There is another aspect of the matter,” said Mr Gorringer. “I have the good name of the school to remember. Our coastal resorts seem just now to provide an abundance of such cases as we wish Deene to avoid. Can we not conspire to suggest Malvern perhaps? Tunbridge Wells? Cheltenham Spa? Harrogate? They seem pleasantly free from the deeds of violence by which our patient is attracted.”

“I daresay an inland resort would be just as good for him,” admitted the doctor. “I could send him to Buddington-on-the-Hill, if you like.”

“I should be immensely obliged,” said the headmaster. “Immensely. It is, I believe, a quiet little town in peaceful surroundings.”

“All right,” said Dr Thomas, rising. “I’ll tell him. There’s a passable hotel there.”

“Do you not think a nursing home might be preferable?”

“It might, but Carolus wouldn’t stay in it. I must run. I’ll do what I can.”

But this did not altogether reassure the headmaster. He was noticeably thoughtful during the morning and when he passed the music master in the cloisters his “Ah, Tubley …” seemed positively absent-minded.

Towards the end of the afternoon he again summoned Muggeridge.

“At what time is the evening paper on sale?” he enquired.

“It’s out now,” said the porter. “But I can tell you what won the two-thirty.”

“Do not be impertinent,” said Mr Gorringer. “You are perfectly aware that I take no interest in horse-racing. It would ill befit my position.”

“I don’t know. Some of them do all right,” said Muggeridge darkly.

“You are not referring to the staff, I trust?”

“Hollingbourne brought up a double yesterday. But he’s not often lucky. Some of the boys study form better than him.”

Mr Gorringer controlled himself, for he was anxious to know more.

“Really?” he said with elephantine casualness. “That surprises me.”

“It didn’t ought to. Young Priggley’s a consistent winner. I feel like following him sometimes.”

“That will do, thank you, Muggeridge. Now kindly purchase the evening paper, which I need for quite different reasons.”

The porter sighed and went out while Mr Gorringer made a note in the small pocket-book he carried. ‘See Priggley. Horse-racing’, it ominously read.

When his newspaper came he studied it with care. He found that at Torquay, where a family of three had apparently been killed by poisoning, the person previously questioned had now been charged with murder. He was, according to the news-sheet, a wealthy numismatist from Gateshead. At Bournemouth the man with his arm in plaster had been taken to the local police station and was still there ‘up to a late hour’ last night. The Scarborough case looked even more open-and-shut and ‘the woman’, a Birmingham housewife, had been remanded in custody.

Mr Gorringer sighed and after glancing at his watch set out for the school sanatorium. His best course, he felt, was to see Carolus Deene for himself and if necessary make a personal appeal. He did not want his anxiety to last throughout the coming Easter holidays, which he planned to spend as usual at the Sandringham Private Hotel at Brighton. He dreamed of a promise from Carolus Deene which would allay his fears.

He found his Senior History Master sitting up in bed reading Lucas’s Forensic Chemistry and Scientific Criminal Investigation.

Carolus Deene was in his early forties. He had been a good all-round athlete with a half blue for boxing and a fine record in athletics. During the war he did violent things, always with a certain elegance for which he was famous. He jumped out of aeroplanes with a parachute and actually killed a couple of men with his Commando knife which, he supposed ingenuously, had been issued to him for that purpose.

He was slim, dapper, rather pale and he dressed too well for a schoolmaster. He was not a good disciplinarian as the headmaster understood the word because he simply could not be bothered with discipline, being far too interested in his subject. If there were stupid boys who did not feel this interest and preferred to sit at the back of his class and eat revolting sweets he let them, continuing to talk to the few who listened. He was popular, but considered a little odd. His dressiness and passionate interest in both history and crime were his best-known characteristics in the school, though among the staff his large private income was a matter for some invidious comment.

“Ah, Deene,” said Mr Gorringer, “making good progress, I see.”

“Yes thanks, headmaster. Do find a seat.”

“I notice you are doing a little light reading.”

“Yes. It’s not bad,” said Carolus. “Sorry I shan’t be able to do my stuff with the exams.”

“Truly a pity. But jaundice is jaundice. I hear that Dr Thomas is recommending you to go away for a period of complete rest.”

“Sounds as though I’d had a nervous breakdown. Yes, Tom did say he thought I ought to have a change of air.”

“Where did you think of going?” asked Mr Gorringer, keeping his voice as casual as possible.

“It doesn’t seem to matter. Doctors have given up pretending that one resort is better than another, I gather.”

“He did not recommend any particular spa for you?”

“He said something about Buddington-on-the-Hill, I believe. But it sounded deathly dull.”

“An excellent choice, my dear Deene. A splendid little place. It would build you up in no time, I feel sure.”

“I don’t really mind. Tom says there’s a reasonably good hotel there.”

“I rejoice to hear it. You will no doubt make reservations there forthwith?”

“I suppose so.”

Mr Gorringer wished him a quick recovery and left with a lighter heart. When, four days later, he heard that the school doctor had himself driven Carolus to Buddington and returned to say that he was comfortably settled at the Royal Hydro, and would remain there for at least three weeks, the headmaster could read of the deepening mystery at Torquay, the police baffled at Bournemouth, the surprising developments at Scarborough without losing his large appetite.

On the Saturday after the departure of Carolus he decided to take his History Master’s place and conduct a lesson with the Lower Sixth, a difficult class dominated by that odiously sophisticated boy, Rupert Priggley. Mr Gorringer found that Carolus had left the class deep in the affairs of the fourteenth century.

For the headmaster history was firmly divided into ‘reigns’ and he tackled that of Richard II with a will. He found the class curiously attentive as he ran through Richard’s wily tactics, his sudden arresting of his opponents and finally his own deposition.

“Parliament ordered that Richard should be imprisoned,” pronounced Mr Gorringer sonorously as he secretly wondered how this class had gai

ned a reputation for unruliness. “He was privily removed from the Tower of London and sent to Pontefract Castle. He lived through most of the winter, but in February he died.” Mr Gorringer paused to prepare his final peroration.

A boy named Simmons, a studious and bespectacled youth, devoted to study, the headmaster believed, asked a question.

“What did he die of, sir?”

It was innocently spoken.

“History does not record …” began Mr Gorringer.

“Wasn’t he starved to death, sir?”

“Wasn’t it straight murder, sir?”

“Why was his corpse never shown to the people as Parliament ordered, sir?”

“What exactly was the mystery, sir?”

Mr Gorringer looked about him, realizing too late the guile of the innocent-looking Simmons.

“It does not seem to be a point of much historical interest,” he said airily. “Privation of one sort or another, no doubt.”

“Murder, then?” suggested Priggley.

“Murder, mayhap, neglect, discomfort, illness, starvation. Who is to say?” asked the headmaster rhetorically.

“Mr Deene, if he were here,” retorted Priggley. “It would be just his cup of tea. He’d probably run down to Pontefract looking for clues.”

“That will do, Priggley. We will now …”

“You must own it’s most unsatisfactory, sir. Here’s a king just petering out, as it were. One should know at least whether he was assassinated.”

“When your History Master returns to his duties you will no doubt be able to inveigle him into speculation on that wholly irrelevant point …”

“It wouldn’t be irrelevant to him, sir. It would be the point. Who did it. How. Why. When. Where. Right up his street.”

“Silence, sir!” said Mr Gorringer in an intimidating voice. “Let us now consider the character of this sovereign and its effect on contemporary events …”

The lesson went on without further interruption and Mr Gorringer was able to dismiss the class with good-humour.

As he was walking home half an hour later he found Priggley in wait for him. In the boy’s hand was a copy of the evening paper.

Nothing Like Blood

Nothing Like Blood Death of a Bovver Boy

Death of a Bovver Boy Jack on the Gallows Tree

Jack on the Gallows Tree Case with No Conclusion

Case with No Conclusion Case for Three Detectives

Case for Three Detectives Furious Old Women

Furious Old Women Death of a Commuter

Death of a Commuter Case with Ropes and Rings

Case with Ropes and Rings Dead Man’s Shoes

Dead Man’s Shoes Case with 4 Clowns

Case with 4 Clowns Death with Blue Ribbon

Death with Blue Ribbon Death in Albert Park

Death in Albert Park Die All, Die Merrily

Die All, Die Merrily Death in the Middle Watch

Death in the Middle Watch Death at St. Asprey’s School

Death at St. Asprey’s School Case for Sergeant Beef

Case for Sergeant Beef