- Home

- Bruce, Leo

Case for Sergeant Beef Page 2

Case for Sergeant Beef Read online

Page 2

Now I remember many years ago during a walking tour in Kent finding a village called Barnford. It was a pleasant village with oldish red-brick houses and a square church tower. And near it was a wood through which ran a public footpath. I have been thinking that this will make the ideal spot. Lonely, but one could be sure of someone coming along sooner or later. Plenty of cover, before and after. The body to be found quickly if one wanted it found quickly, or not for a long time, if one wanted it concealed. And the sort of area in which I might well be living in the unlikely event of my having to give an account of myself. I shall go down there to-morrow and prospect.

Third Entry

I have been luckier than I could have hoped. I found an empty bungalow at Barnford, right on the outskirts of Dead-man’s Wood. (Yes, that is actually its name. Is it not appropriate? I could scarcely repress a smile when I heard it!) The bungalow is called ‘Labour’s End’, which again is very fitting, as I said quite truthfully that I wanted to retire and grow roses. The soil, I am told, is splendid for them. I have bought the little place not too expensively – I am in any case not perturbed by the outlay as I shall certainly stay there even after the Great Event. It will be pleasant in my declining years to visit the scene of my triumph.

I shall have a few neighbours. On the other side of the wood lives a Miss Shoulter who breeds spaniels – far enough away, I learn, for their yelping to be inaudible. And in the wood itself there is a larger house in which a family named Flipp lives. But they have their own way in from the road and do not use the footpath I remembered.

That footpath is just as I hoped – a narrow rather winding track between the trees which cuts right across the wood from near Miss Shoulter’s bungalow to mine. I could be walking along it at any time of day or night without arousing the faintest suspicion, even on the night of a murder. Yet it is lonely enough to provide a dozen points at which the thing could be done, and done in the confidence that there were no witnesses. Ideal. I hope to move in next week.

Fourth Entry

I am comfortably established at Labour’s End. It is really a very pleasant little house overlooking a sweep of country only cut by the railway line nearly a mile away. I have brought my own furniture down after it had been in store three years, since, in fact, I sold my business.

Mentioning that reminds me that I should give some account of myself, for when the facts about my murder come out after my death, it is certain that there will be a good deal of research into my past and the results may not be accurate. I want the true facts to be known.

I was an only son. My father was employed by a firm of stonemasons, and spent his life in chipping at memorial crosses for people who deserved no memorial. He was, by the standards of his time, well paid, and our little home in South London though dingy and cramped never knew the miseries of want or hunger.

I was given a better education than most sons of artisans and remained at school till I was nearly seventeen. Then I was apprenticed to an old watchmaker, a friend of my father, who taught me the trade which has served me ever since.

My father was an honest decent man, but an incurable sentimentalist with a taste for military history. He could reconstruct almost every battle fought by British armies and would bore his fellow customers in the saloon bar of the Mitre, which he ‘used’ for forty years, with detailed accounts of Waterloo or the Nile, until they told him to come off it. It was this passion of his which caused him to name me after the Iron Duke, and it was an unfortunate choice considering our curious surname. And when I failed to grow above five feet four inches it seemed even more out of place. However, both my father and my mother, a plump easy-going woman who took me to chapel on Sundays, delighted in it, never abbreviated it and could be heard shouting ‘Wellington!’ down our back-garden when they wanted me to come indoors.

At twenty-five I started my own watchmaking business in what was then a little town separated from London by open country, but which became, I’m glad to say, one of the busiest suburbs. My little shop thrived, and a quarter of a century later, when I was employing a dozen men and women and had a fine establishment, I sold it at the top of the market and retired on the proceeds, together with my not inconsiderable investments.

I forgot to say that I married at thirty a girl who brought me the initial capital I needed for enlarging my business. She failed to bear me a child and died some years before I retired.

Since I sold the shop I have been living in rooms, waiting for a chance to settle in the country.

That is my uneventful story and from it you will see, perhaps, why I have made up my mind to distinguish myself now. The man who bought my business has already changed the name, so that unless I achieve my great ambition no one twenty years hence will have heard of Wellington Chickle. But I shall achieve it.

CHAPTER THREE

Journal of Wellington Chickle

Continued

Fifth Entry

I have been unpacking and arranging my books. It is a pleasant task, although my anxiety to get them all into place so that I can refer to them easily has made me overtire myself a little. My library consists entirely of criminology in all its forms and I have spent a great deal of money over many years in accumulating it. Old Trials, the Newgate Calendar, Lives of the Highwaymen, a formidable row of books on Criminal Jurisprudence, and everything that is worth while in modern detective fiction, from Poe and Gaboriau down to Bentley and Agatha Christie. I am really proud of some of the more unusual items, and get great amusement from dipping into the Famous Trials series and seeing the idiotic mistakes made by blundering murderers of the past. How little finesse most of them possessed. They approached the delicate matter of murder as though it were a pick and shovel job and allowed their passions to betray them into every kind of impatience and risk. I smile when I realize my superiority over that sort of violence, for in my crime there will be no passion and so no risk at all.

I took a walk along the footpath through Deadman’s Wood to-day, and found it bright with bluebells. I should like my murder to be in spring, I think, while these beautiful blue flowers make a shining carpet underfoot. Only I should have to be careful of trampling them in any indicative way. However, I have not begun to consider such details yet. I am still concerned with the Place and I think I have found it. A fallen tree beside the path would give excellent concealment and it is roughly half-way through the wood at a point where the trees on either side are thickest. With tremendous inward excitement I decided to test the hiding-place behind that tree and to find out whether one could see a person approaching. I crouched down and peered over the trunk. Excellent. At dusk I should be quite invisible and should see anyone from at least twelve yards away. Exactly as I hoped.

My enjoyment was irritatingly interrupted by someone approaching from the other direction, and you may imagine my annoyance when I found it was the pasty-faced curate from Barnford walking alone through the wood. And he was tactless enough to smile when he saw me crouching there. Really it is a good thing for him that I have decided that my victim shall be quite unknown to me, for I could have killed him for his cheerful loquacity.

‘How do you do?’ he asked. He might as well have said, ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’

‘How d’you do?’ I answered with assumed good humour.

‘Picking bluebells?’ he asked.

‘I was just about to,’ I said. ‘Lovely, aren’t they? As a Londoner I find your countryside most attractive.’

And what must he do but start a long conversation while I brushed the leaves and a little dirt from my clothes. He came from London too it appeared, from Sydenham to be precise. He had only been here two years and remembered his first spring in Kent, so he knew just how I felt. The fool. If he knew just how I felt he would know that I wanted to assassinate him for his…smugness then and there.

And of course he turned the conversation to me. Where did I live? What was my name? Would I be attending his church?

To the last question I

replied solemnly that indeed I should, every Sunday, for I realize that this will be an important part of the character I am creating for myself. A nice old church-going retired tradesman. Not chapel, I feel, and certainly not Roman Catholic. Too suggestive of earnestness or even violence. Church of England is the safest bet – so wholly non-committal and yet so thoroughly respectable. I invited the curate back to tea and flattered myself that I appeared delighted to watch him satisfying a phenomenal appetite. No wonder he has a pasty look, and that his ears are bright red. Constipation, undoubtedly.

Sixth Entry

Really, considering it’s only about six weeks since I first began to make definite plans, I think I have done very well. I have found the district, and the very point in that district for my purpose. Though I had all the British Isles to choose from I am satisfied that the spot I have finally selected could not be better. And I have so arranged matters that I have a perfectly natural reason for being near that spot at any time of day or night. I live here. Not bad for so short a time.

I must now go on to consider the method, and I need scarcely say that I have been giving very careful thought to that. Poison is out of the question, for the thing must of course be spontaneous. Poison means endless preparation and precaution for the layman, endless risk in obtaining it, endless trouble in administering it, and endless difficulties in making it appear as suicide. Besides if I am to murder my man at that point in Deadman’s Wood (how I delight in that name) poison is unthinkable. What would I be doing standing there offering prussic acid to a chance pedestrian? It’s absurd.

Nor do I need to employ any of those elaborate death machines so popular in murder stories, poisoned darts blown from pipes, injections, or poisoned scratches, weights timed to drop on unsuspecting crania – these are all the inventions of less fortunate murderers who have to wipe out a certain person at a certain time and place, and establish their own alibis. All quite unnecessary for me.

Strangling and suffocation are ‘out’ too, if for no other reason than that of my inadequate height and strength. Drowning is of course out of the question, and such chancy things as bows-and-arrows or boomerangs I prefer not to consider. Then again I am not powerful enough for clubbing or smashing the head with some gardening tool like a spade, and an axe seems to me a clumsy weapon more suited to early warfare than to a brilliantly-planned twentieth-century murder.

This brings me to a choice of two classes of weapon, a blade or a firearm. Each has its advantages of course. The blade, whether sword, spear, knife, dagger, or razor, is silent, but the gun is sure. At least it will be in my hands. For twenty years the only relaxation I have known from the work of my shop has been a little rough shooting I have had in Essex. I hired it with an old friend called Whitman, and we would miss very few week-ends. With a good 12-bore on that path I could be as sure of my man as the hangman is of his. But of course, there’s the noise, and the possession of a gun and many other factors. It will need a great deal of consideration.

Meanwhile Miss Shoulter has called – at least I suppose it was a call I was working in my garden this afternoon when I heard what I took to be a man’s voice shouting from the gate.

‘Hullo! Are you Mr Chickle?’

I straightened up and saw a woman with a long sunburnt face and shapeless check tweeds standing there with two spaniel puppies on leads. I never forget my character as that of an amiable old gentleman, and walked across to her smiling in the most friendly way.

‘I am, and you must be Miss Shoulter. Do come in.’

‘ ‘Fraid I can’t,’ she yelled in that ear-splitting male voice of hers. ‘Got the pups with me. Thought I’d just come and say hullo, as we’re neighbours.’

‘That’s very good of you,’ I smiled.

Then she kept me talking there for five minutes, though I was impatient to get back to my flower-bed. Maddening woman. Why should she think I am interested in her dogs? I asked her at last why she didn’t breed retrievers.

‘Why? Fond of shooting?’ she said. Such a direct question. I was taken off my guard.

‘No,’ I said. Then I built up a bit more of my character. ‘I couldn’t bear to hurt live creatures,’ I added.

‘No need to do that,’ she shouted. ‘Been shooting all me life and don’t believe I’ve caused any pain. Not as much as nature causes with her ways of killing, anyway.’

‘Do you do any shooting now?’ I asked.

‘Not much. I’ve got a couple of guns still.’

‘Perhaps you feel that living alone …’ I began. But she gave a great vulgar hoarse laugh.

‘Me? I can look after myself without guns,’ she said. And looking at her I thought it only too likely to be true.

A minute later she was gone, leaving me quite a lot to think about.

Seventh Entry

I have engaged a housekeeper, an excellent woman named Mrs Pluck. I am paying her rather large wages, but she is more than worth it, for she is not only a splendid cook with a passion for keeping the house scrupulously clean, but she has what almost amounts to a mania for punctuality. Although she carries a wrist-watch her first request was for a kitchen alarm clock and she seems always to keep an eye on the time. This will one day serve my purpose, I feel sure. If I can depend on her to notice the times of my comings and goings the day will come when she will provide an alibi.

She is, I must admit, slightly forbidding in manner and appearance, nearly six feet in height and with a face that might justly be called gaunt. She appears to be extremely muscular and her hands are as large as those of a man, with powerful bony wrists and fingers. However, I have no wish for personal beauty in a housekeeper. Her other qualities are an ample compensation for her severe mien.

I thought I would test her to-day.

‘What time was it when I came in?’ I asked very casually when she was laying the table for my simple evening meal.

‘Just five minutes to six,’ she said sharply, without pausing to remember or consider at all.

What could be more precise or satisfactory?

‘Thank you, Mrs Pluck,’ I said. I’m afraid I’m a bit vague about time. You must keep me up to scratch, you know.’

‘Your meals will always be ready on time,’ she said rather grimly and left me to sip the sweet sherry of which I have always been so fond.

Eighth Entry

I learnt something to-day which, if it is true, will mean that my decision in the matter of weapons has been made for me. A man called Richey, whom I have engaged to work in the garden two days a week, mentioned that the last tenant of ‘Labour’s End’ had rented the shooting in Dead-man’s Wood for an absurdly small price from the owner, who lives a dozen miles away.

‘He only paid a pound or two for it,’ Richey said. ‘Because there’s nothing there. A few rabbits you might get and a left-over pheasant or two from the time they did preserve. But nothing to pay money for. Still if you think you could find any sport.’

I laughed inside myself. If I think I could find any sport. Richey would be surprised if he knew what sport I think I could find.

But it’s an idea. If I do decide that a gun is the best weapon – well, there I am with a gun, and every right to be there. And if a man is found shot in Deadman’s Wood it would have been an accident, or suicide, or somebody else. It could not possibly have been that little quiet studious man Mr Wellington Chickle. Why should it have been? What motive could he possibly have had?

I only wonder whether perhaps I’m getting away a little from my original conception – the spontaneous crime. I remember writing in this Journal that if a man of good character suddenly killed the first person who came along, unless he was actually seen in the act he could not be suspected. But am I beginning to complicate matters? I don’t think so, really. I’m giving myself a reason for being in the place with the weapon in case I should be observed.

I am writing this evening to the owner of the shooting rights to see whether an arrangement can be made. If it can I think I�

�ll decide on the gun. All details can wait for that.

Mrs Pluck gave me an excellent soufflé this evening. Really, that woman’s a treasure. And when I enquired gently what time it was when I went to bed last night she answered me pat- Eleven-twenty, sir. I heard you close your door.’ So even in the night hours she notices what time things happen.

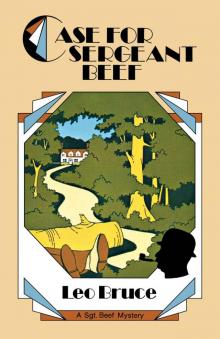

Some new books arrived from Bumpus’s to-day, or rather some old books they had been able to obtain for me. Among them some detective novels by a writer new to me – Leo Bruce. He relates the investigations of a certain Sergeant Beef, through an observer called Townsend. Very ingenious. But not as ingenious as I’m going to be. I should like to see Sergeant Beef at work on my crime!

CHAPTER FOUR

Journal of Wellington Chickle

Continued

Ninth Entry

I met Flipp and his wife to-day. Another piece of luck – Flipp is fond of shooting and goes down to the marshes, somewhere Rye way I gather, for duck when he can get petrol for his car. Hasn’t done much since the war, but says he has a 12-bore. So that’s three in the district – mine, Miss Shoulter’s, and his. It begins to look as though the whole thing is being made too easy for me.

Flipp is a big man who is in some business in London which does not take too much of his time. He goes up to town twice or three times a week, I gather, and does not worry if he misses even that. If it is of any interest I can easily find out the nature of this business. He looks more like a farmer, a heavy hard-drinking man, who swears too much, even using rather strong language in the presence of his wife. She, poor woman, looks anaemic, a frost-bitten unhappy creature very much under Flipp’s thumb.

Nothing Like Blood

Nothing Like Blood Death of a Bovver Boy

Death of a Bovver Boy Jack on the Gallows Tree

Jack on the Gallows Tree Case with No Conclusion

Case with No Conclusion Case for Three Detectives

Case for Three Detectives Furious Old Women

Furious Old Women Death of a Commuter

Death of a Commuter Case with Ropes and Rings

Case with Ropes and Rings Dead Man’s Shoes

Dead Man’s Shoes Case with 4 Clowns

Case with 4 Clowns Death with Blue Ribbon

Death with Blue Ribbon Death in Albert Park

Death in Albert Park Die All, Die Merrily

Die All, Die Merrily Death in the Middle Watch

Death in the Middle Watch Death at St. Asprey’s School

Death at St. Asprey’s School Case for Sergeant Beef

Case for Sergeant Beef